Storm clouds gathering? Inflation and high-interest rates

A view from the INREV Autumn Conference 2022

Paul Kennedy, Managing Director, Portfolio Manager, Global Alternatives, J.P. Morgan Asset management discussed the outlook for inflation, interest rates and what does it mean for main asset classes at the INREV Autumn conference in Marseille.

The combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has reignited inflation. The key question as we look to 2023 is whether a modest economic slowdown or mild recession will be enough to get rid of inflation; or whether we have returned to the 1970s and it will take much higher interest rates and deep recession to bring it down.

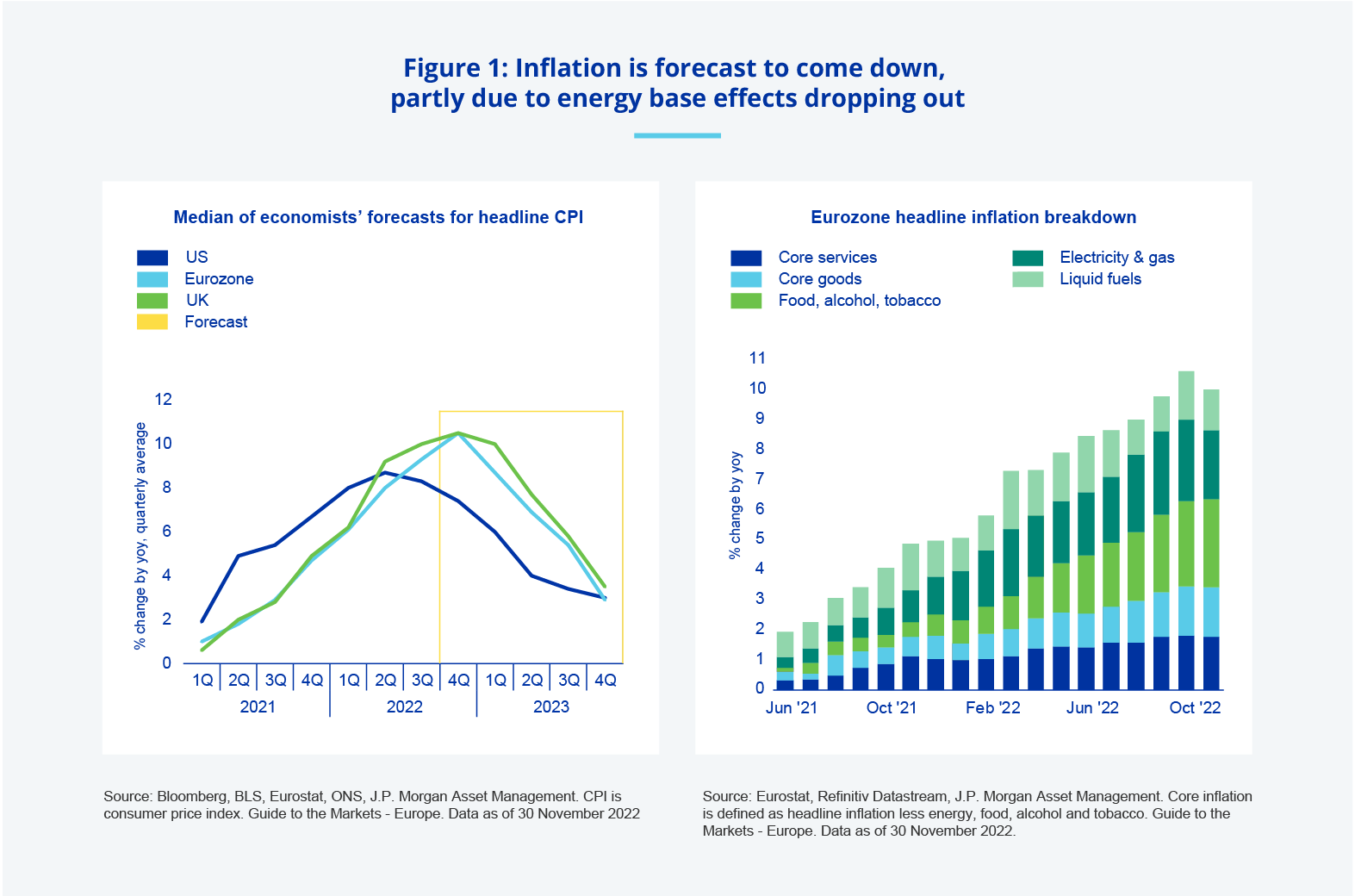

The good news is that the inflation is forecast to calm down as energy base effects start to drop out. In Europe consensus expectations are for inflation to peak in Q4 2022 and fall from there. This contention is supported by a number of data points. First, the falling base effects of energy should support gradually lower prices through 2023 and into 2024. This trend should be reinforced by a broad-based reduction in commodity costs, including steel and timber.

Clear signs of supply side pressures easing provide further reassurance. The disruption to delivery times triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be easing with supplier delivery times returning to long-term trend levels. At the same time the costs associated with container freight have fallen and any degree of China’s reopening would help to reinforce this trend, potentially helping to bring costs back down to trend levels.

If the current forecasts are correct and inflation cools, central banks might not have to act so aggressively. While reduction in rates are unlikely until at least the end of 2023, success in fighting inflation could mean that markets reassess their outlook, and shift to a more rapid and dramatic easing of policy. That said, the era of ‘lower for longer’ is over. Higher long-term rates will provide Central Banks with ammunition to address future economic crisis; they will also reduce the risk of excessive monetary stimulus triggering asset price bubbles. The bottom line is that this change will have important implications for the pricing of all risk assets, including real estate.

The era of ‘lower for longer’ is over. Higher long-term rates will provide Central Banks with ammunition to address future economic crisis; they will also reduce the risk of excessive monetary stimulus triggering asset price bubbles

While one should not expect the transition back to trend inflation to be painless, the impact should be mitigated by two factors: first, the reduction of energy and other commodity prices; and second, the relative robustness of the eurozone and, to a lesser extent, UK economies.

The labour market remains very tight, with unemployment rates close to all-time lows while job vacancies remain elevated. A weaker labour market is a prerequisite for lower inflation and there are first signs that this is well underway, as vacancies come off their peaks and unemployment rates plateau. However, the labour market’s strong starting position means household incomes and consumer spending should remain resilient. This will help to mitigate the potential economic downside.

In the eurozone excess savings are at an all-time high, supporting the case that household incomes and consumption should be resilient to the impact of the higher rates and living costs associated with the period of elevated inflation.

In contrast to the eurozone, the recession in the UK is expected to be more protracted

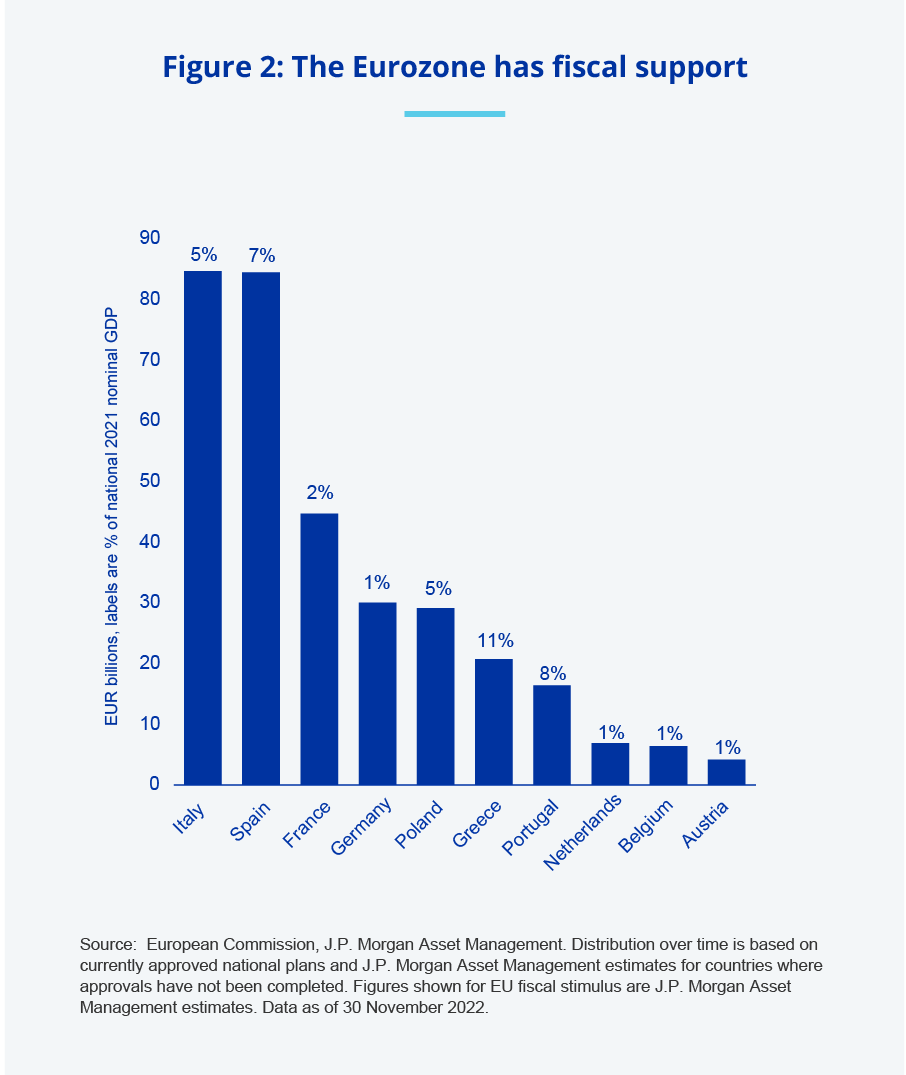

Further comfort to all this lies in the fact that the eurozone has fiscal support and has learnt from past mistakes. The return of government spending and clear eurozone fiscal co-ordination is a key change, particularly given the painful experience of limited fiscal co-ordination post-GFC.

EU Recovery Fund grants to range from 8% to 1% of national GDP in aggregate and range from €84bn to €4bn depending on the country. These flows should provide a valuable offset to the challenges to household and corporate balance sheets associated with rising interest rates and energy costs.

Marked reductions in gas prices to date suggest further scope for downward pressure on inflation in both the eurozone and the UK. This is helped by mild weather to date, which has reduced demand, contributing to the downward pressure on gas prices.

In contrast to the eurozone, the recession in the UK is expected to be more protracted. Differences in business investment and, to a lesser extent, fiscal support provide an explanation of the different outlooks for real GDP growth.

While rising bond yields will inevitably lead to a change in the return drivers of real estate – with income returns becoming increasingly important – this will mark a reversion back to a more traditional and sustainable role for the asset class

For the eurozone, JP Morgan Asset Management expects real GDP growth to be negative between Q3 2022 and Q1 2023. In the UK, negative GDP growth is expected to last six months longer, from Q3 2022 until Q3 2023. UK real GDP growth is likely to remain substantially below trend until Q1 2024, although the recovery in 2024 should be relatively robust when compared to the eurozone – reflecting the more volatile nature of the UK economy.

Turning to stock markets, there is a growing difference between price growth and earnings. While the former has corrected markedly, the latter is lagging. Although corporate earnings remain robust the stock market is pricing in a substantial correction; this suggests that stock prices have either already settled or are relatively close to doing so. As a result, the correction in equities that was seen through this year has set the stage for a marked improvement in long-term returns.

At the same time, the markets have recorded a sharp repricing of global bond yields to levels not seen in recent decades. The yield on global aggregate bonds have increased from under 1% in 2021, to over 3.5% toward the end of 2022. If the current consensus is right and inflation is close to peaking, then the stage is set for bonds to deliver meaningfully higher returns.

All in all, the long-term stock-bond frontier has shifted favourably for public markets, leaving real estate behind. Real estate has shifted from being an out-performing asset class, to underperforming – at least at the aggregate level. At the same time the upward shift in bond yields means that real estate’s role as an income substitute for low yielding bonds has become less important.

Nevertheless, real estate retains some clear advantages. It is a real asset class in an environment of elevated and uncertain inflation. It offers important diversification benefits and scope for informed investors to add value to assets. In addition, changes to the key drivers of occupier demand associated with e-commerce, hybrid working and ESG offer exceptional opportunities to drive returns through insightful sector and stock selection.

Perhaps more importantly, the more protracted period of price discovery in private markets, including real estate, means that prospective returns can appear to be lagging public markets. However, as prices adjust, opportunities will inevitably improve. Finally, while rising bond yields will inevitably lead to a change in the return drivers of real estate – with income returns becoming increasingly important – this will mark a reversion back to a more traditional and sustainable role for the asset class.